Most of us have at least heard of wine tannin. But what is it, exactly? And how does it affect our perception of wine?

What Are Wine Tannins?

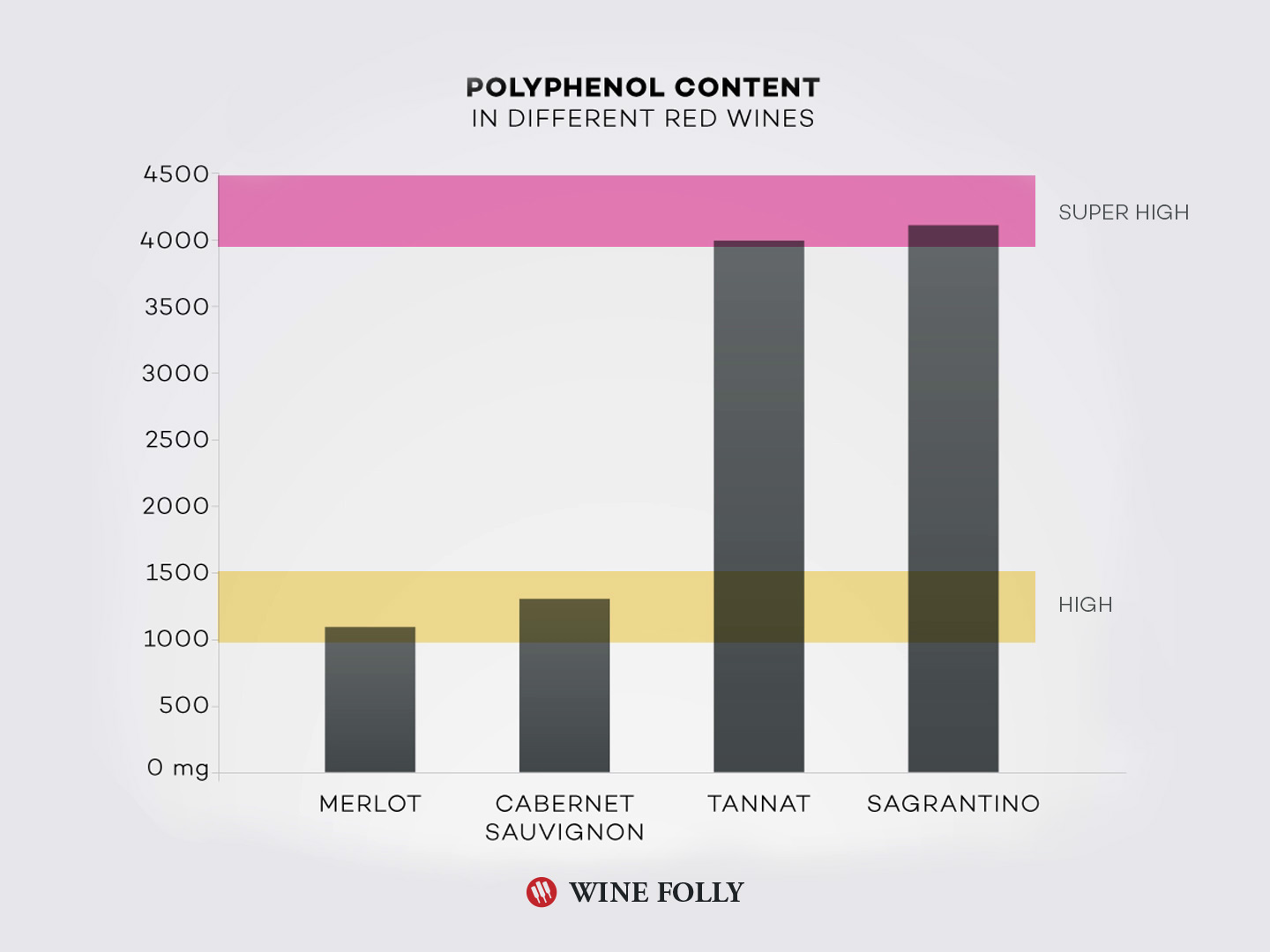

Tannin is a naturally occurring polyphenol found in plants, seeds, bark, wood, leaves, and fruit skins.

Polyphenols are macromolecules made of phenols, which are complex bonds of oxygen and hydrogen molecules. (Yep, wine is science!)

The term “tannin” comes from the ancient Latin word for tanner and refers to the use of tree bark to tan hides.

What Do Wine Tannins Taste Like?

Tannin in wine adds both bitterness and astringency, as well as complexity. It is most commonly found in red wine, although some white wines have tannin too (from aging in wooden barrels or fermenting on skins).

Need an example? Put a wet tea bag on your tongue. About half of the dry weight of plant leaves is pure tannin.

Other foods with tannin:

- Tea leaves

- Walnuts, almonds, and other whole nuts (with skins)

- Dark chocolate

- Cinnamon, clove, and other whole spices

- Pomegranates, grapes, and açaí berries

Are Wine Tannins Bad For You?

No: in fact, wine tannins are likely good for your health.

There is actually a study on the effects of wine and tea tannin on oxidation in the body. In the tests, wine tannin resists oxidation, whereas tea tannin does not. In other words, it’s an antioxidant.

What about migraines? The jury is still out on the connection between tannin and migraines. To remove them from your diet, you’d need to stop consuming chocolate, nuts, apple juice, tea, pomegranate, and wine.

While wines with pronounced tannin can seem harsh and astringent on their own, they can be the best possible partners for certain foods and are a key ingredient in a wine’s ability to age well.

What Wine Has The Most Tannins?

Red wines have more tannins than white wines, but not all red wines are equal. Here are some examples of high-tannin red wines:

- Tannat: Uruguay’s most planted grape, Tannat is known for having some of the highest polyphenols of all red wines.

- Sagrantino: A rare treasure of central Italy, Sagrantino stands neck and neck with Tannat with its extreme tannin content.

- Petite Sirah: Originally French, Petite Sirah and its powerful flavors are now largely found in California.

- Nebbiolo: One of Italy’s most legendary grapes, Nebbiolo boasts high tannin content and bitterness while still having a delicate nose.

- Cabernet Sauvignon: You know this one. The most widely planted grape in the world is known for velvety tannins and high aging potential.

- Petit Verdot: Known best as one of Bordeaux’s red blending grapes, Petit Verdot offers a floral, smooth sense of tannin.

- Monastrell: Popular in Spain and France, Monastrell (aka Mourvèdre) has a smoky, bold sense of tannin.

It’s helpful to remember that winemaking style greatly affects the amount of tannin in a wine. In general, high-production wines are deliberately created to have rounder, softer-feeling tannins.

Pairing High Tannin Wine with Foods

The astringency of tannin is a perfect partner for rich, fatty foods.

For example, tannin cuts through the intense meaty protein of a dry-aged fat-marbled steak, permitting subtler flavors of both wine and food to emerge. The tannin molecules bind to proteins and other organic compounds in the food and scrape them from your tongue. Wow!

Learn more about how to pair wine and food.

What Red Wine Has No Tannins?

The very process of making red wine means that all red wines have tannins. If it’s red, there are tannins, period.

In fact, there are tannins in white wine as well! However, because most white wines are immediately pressed rather than macerated, the amount of tannin from their skins and seeds is usually quite low.

Looking for low tannin red wines? Check out this article about the softer side of red.

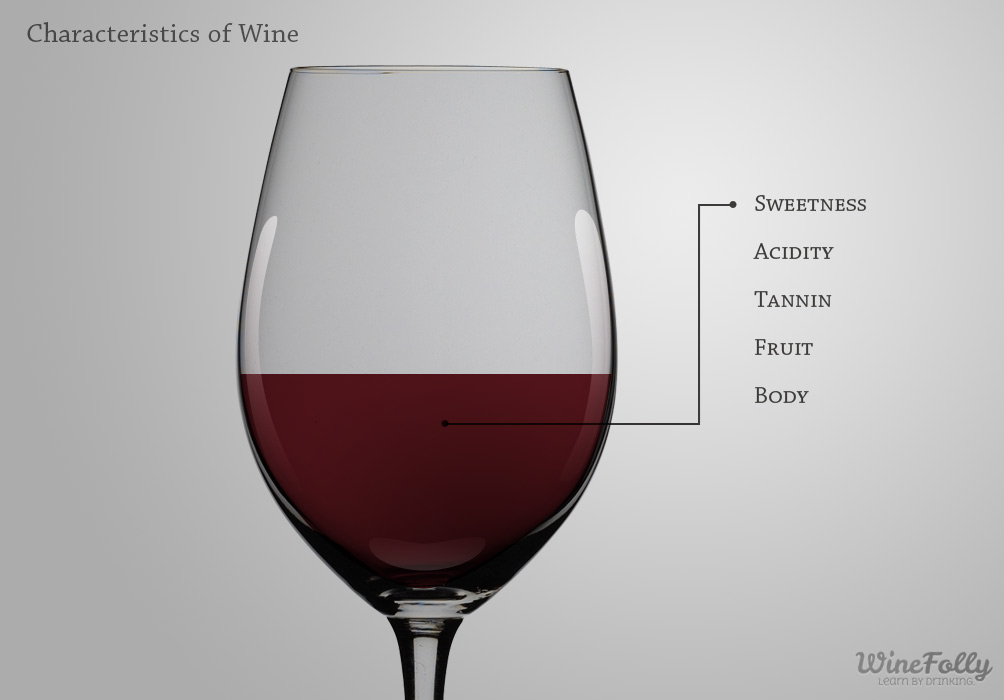

How Do Tannins Help Balance Wine?

When it comes to finding the best wines, most experts will tell you that the key lies in balance, essentially, the key qualities of wine complementing each other seamlessly. Tannin (which also helps give a wine structure) is one of those key qualities, along with acidity, alcohol, and fruit.

Actually, Tannins Help Wines Age Well

Despite the shocking astringency that high-tannin wines have when they’re young, this is one of the key traits that allows red wines to age well for decades.

Over time, those big, bitter tannins will polymerize, creating long chains with each other, causing them to feel smoother and less harsh.

It’s one of the key reasons that a young, powerful wine like Brunello di Montalcino is often aged for as long as ten years before it’s opened.

Of course, some people really enjoy all that bitterness! But to collectors, a well-aged wine with heavy tannins is worth its weight in gold (sometimes literally).

Case in Point: Barolo

Take, for example, the 2001 Bartolo Mascarello Barolo, which sold originally for $960 a case. That same case recently sold at auction for $3,472: a 262% increase after 12 years of aging.

So that covers the more rudimentary stuff. But what about the real nitty-gritty? Strap in: this is going to get technical.

Where Do Tannins Come From?

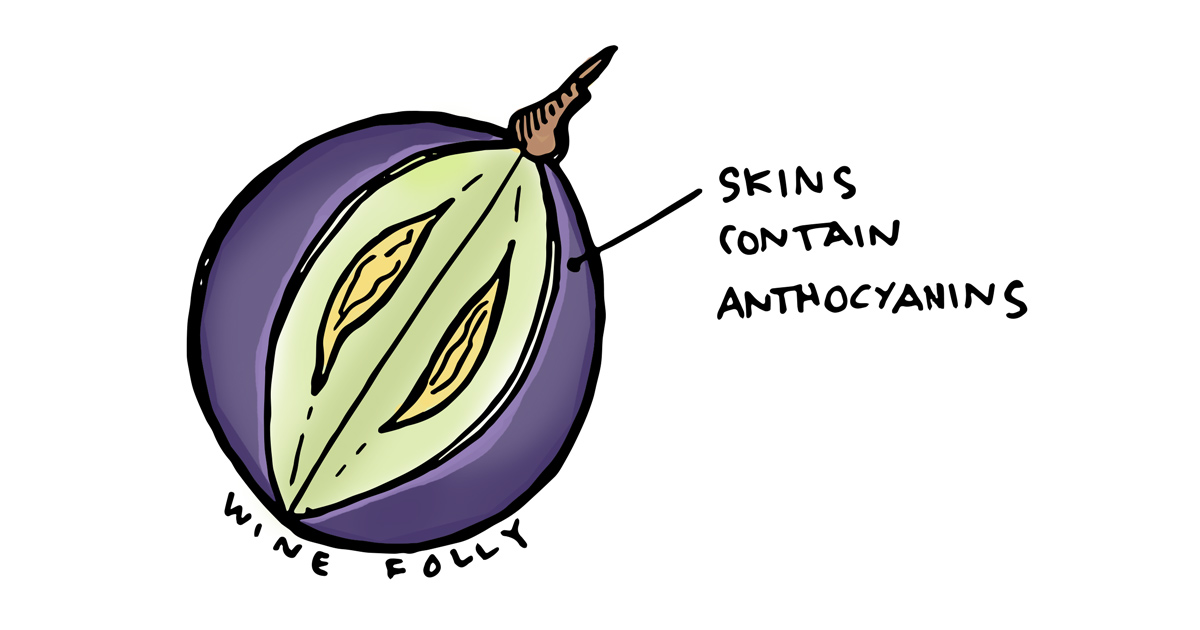

While many plants have tannins, most wine tannins come from grape skins, seeds, stems, and wood. When it comes to making wine, tannins from skin and wood are the most important.

Skins, Seeds, and Stems

Most wine tannins come from the skins of the grapes: not the flesh. Therefore, the color needs to be extracted.

This is done by crushing and allowing the berries to sit in the juice (“must”) in a process called maceration. In a “cold soak,” those berries are kept at a temperature below 50°F (10°C) for a period, increasing pigment.

Extraction can be increased using a number of methods, including punching down the thick cap of skins, seeds, and stems at the surface.

Aside from the amount of tannin, the quality of grape skins varies enormously. Pinot Noir has notoriously thin skins, which provides far less tannin than a thick-skinned Syrah.

Thick-skinned grapes require more time and effort to get their stuff out and into the wine.

Stems can add desirable tannic characteristics to a wine. The most important consideration here is that the stems and grapes must be fully ripe and mature so as not to contribute overly harsh green elements to the wine.

When extracting the juice from seeds, it’s important not to overpress or break them, as this would release oil and give the wine a harsh bitterness.

Wood Tannin

In addition to tannins from grapes, additional tannins can come from time spent in wooden barrels, particularly new small (225— or 228-liter) barrels with a medium—to high toast on the inside.

Most Old World producers have traditionally used wooden vessels primarily for their oxidative properties.

Others seek to extract flavors of vanilla, chocolate, spice, and toasted cedar, as well as astringent woody tannins, to give their wines additional layers of complexity and ageability.

Some producers opt to achieve their desired effects with less time and expense by steeping wood chips or wooden staves in the wine; some even add sawdust! Well, dry powdered tannin, but you get the idea.

Other producers think such shortcuts compromise the quality and integrity of the wine.

The most important thing is that the extracted tannin is well integrated with the other components of the wine and that the tannin’s impact does not cover up or outlast the fruit and acidity.

The Wine Science Of Tannins

You may have noticed that not all tannins are created equal. In some wines, the tannins feel quite long, like they’re stretching out over your palate, while others seem short and pointed.

Some seem dry, green, and bitter, while others are sweet and toasty. Some feel soft and dense, others sharp and aggressive.

This difference comes from the fact that there are chiefly two important types of wine tannins: condensed and hydrolyzable (affected by water).

Hydrolyzable tannins are generally absorbed into wine through the barrels it’s aged in. They provide the softer aromas and flavors favored in oaked wines.

Condensed tannins, on the other hand, generally come from seeds, skins, and stems. These tannins are far more bitter and pronounced.

Grape tannins start as individual flavonoids, which quickly bond together (polymerize) to form macromolecule chains consisting of at least two and as many as thirty or more units.

Anthocyanin molecules (the color in red wine) are typically at the ends of the chain, and numerous other polyphenolic compounds are in the middle. And these molecular conga lines are changing and developing all the time.